A woman approached me, following a recent presentation to a group of families on the topic of inclusive equity-based education, to talk about her son’s educational experience. Those of you involved in this work can imagine the scenario.

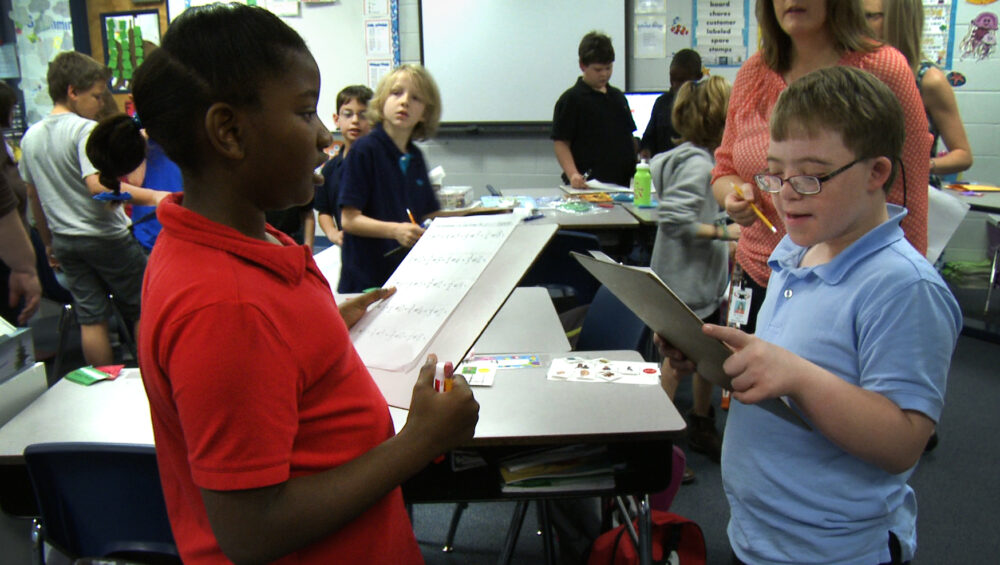

Throughout my presentation, I talked about the 35+ years of research driving this movement; I told story after story of children, families, and school communities who have been positively impacted by All Means All. I described the features that we are consistently finding in schools who have embraced the transformation process to make sure that all students are thriving in general education. I reviewed data, showed films and photos, and discussed tried and true strategies to communicate the importance of all students learning together. I presented the resources of the national technical assistance center, SWIFT (school wide integrated framework for transformation), available to support schools and families on the journey toward inclusive equity-based education.

A consistent theme of my talk was “inclusive education has little to do with the labels and characteristics of students and everything to do with the commitment, creativity, and flexibility of educational teams.”

My post presentation conversation with Ryan’s mother reinforced this theme.

I learned about Ryan, who recently entered middle school. Ryan’s mother wanted to know, “Why is this (inclusive education) so hard for some schools to understand and implement?” She went on to explain that in elementary school, from the time Ryan was in kindergarten, he was fully included in every class. He had friends, learned to ride a bike around the neighborhood, played on recreation sports teams, attended the afterschool program with no additional supports, learned to read and write, rode the regular school bus, and has a label of Down syndrome. And then the transition to middle school changed everything.

When Ryan entered middle school, based on the advice of the education team, he landed in a functional life skills classroom for students with significant support needs. In this situation, he spends the majority of the school day in the classroom working on “life skills,” except for eating lunch in the cafeteria, side by side with other students with disabilities and the paraprofessionals who support them. Ryan’s mother was told he couldn’t participate in the afterschool program without an aide. It is now a few months into the school year and according to his mother, Ryan has acquired a new label – challenging behavior – for his defiance regarding participation in activities with the rest of the life skills class and non-stop talking to himself.

Why did this new label happen? Could it be because Ryan no longer spends time talking and learning with his elementary school friends and is not motivated by the activities of the life skills classroom – as evidenced by the fact that he no longer wants to go to school? Ryan’s mother described the daily challenge of trying to convince Ryan that school was important and that he wasn’t really ill. Might it be because the academic and behavioral/social expectations are dramatically lower than what Ryan was used to? Possibly the lack of appropriate peer models?

More importantly, why did Ryan end up in a self-contained classroom for students with significant support needs? Why does any student end up in such a class? One reason may be years of non-evidenced based traditions and the culture and expectation that students with certain disability labels belong in certain types of classes. “Special” student = “special” class? Another reason may be that because Ryan’s mother was so satisfied with her son’s elementary experience, she had no idea that she had to become a strong advocate to ensure that Ryan’s positive elementary experiences would carry through his transition to middle school.

I listened to this mother’s story and felt sadness. Why do parents of children with disabilities have to work so hard for their children to feel welcomed, valued, and have access to the general education curriculum? When my children, who don’t currently have disability labels, entered middle school, I never questioned what homeroom they would end up in or what teachers they would have. I trusted the educational system to make the best decisions for my children and that my input would be sought as needed. I knew that one of my children would make friends easily and enjoy language arts, social studies, and try out (and not make) the soccer team. I knew that my other child would have more difficulty making friends, would try out (and make) the soccer team, and excel in math and science. I knew that both of my children were welcome in the afterschool program on the days that additional childcare was required. I also trusted that their teachers would guide them through their successes and disappointments as they navigated through these middle school years. Why should Ryan’s mother’s experience and expectations be so different than mine?

As I encouraged this parent to call a meeting with the educational team (including Ryan) and invite allies who could assist in sharing the vision of All Means All and the resources of SWIFT, I felt hopeful. Hopeful that Ryan’s team would trust in their own knowledge and commitment to evidenced based practices in education and fully realize their creativity and flexibility as educators to welcome, value, and support Ryan’s participation in general education.

We continue to learn from our SWIFT partner schools that schoolwide transformation begins with the vision that all children belong and, when given the right supports, all children can learn and excel in general education. 35+ years of research, the lived experience of children with disabilities and their families, and the educators who are transforming schools continue to lead the way toward all really meaning all.

– Dr. Mary Schuh

Dr. Mary Schuh has more than 25 years experience in inclusive schools and communities, family and consumer leadership , and educational systems change and has been with the University of New Hampshire’s Institute on Disability since its inception in 1987. She directs The National Center on Inclusive Education (NCIE) at the Institute on Disability. The NCIE is a leader in the transformation of schools so that students of all abilities are successfully learning in their home schools within general education settings. Mary serves as a member of the National Leadership Consortium of The SWIFT Center. As a faculty member of the University of New Hampshire, Mary helps to prepare future teachers to welcome and engage families, and teach all students in typical school and general education environments.

Dr. Mary Schuh has more than 25 years experience in inclusive schools and communities, family and consumer leadership , and educational systems change and has been with the University of New Hampshire’s Institute on Disability since its inception in 1987. She directs The National Center on Inclusive Education (NCIE) at the Institute on Disability. The NCIE is a leader in the transformation of schools so that students of all abilities are successfully learning in their home schools within general education settings. Mary serves as a member of the National Leadership Consortium of The SWIFT Center. As a faculty member of the University of New Hampshire, Mary helps to prepare future teachers to welcome and engage families, and teach all students in typical school and general education environments.